Right now, all the country’s cinemas are closed, and I’m missing them. My own, particularly, but also just cinemas in general. I’ve been to, I think, 89 different ones in my adult life (yes, of course I’ve got a list), 11 of which have subsequently closed – plus a few more in my childhood (maybe one day I’ll figure out exactly where I saw Star Wars, but that would take more detective work than I feel like right now).

A lot of my favourite film experiences have involved not just the film, but where I watched it, and the total strangers who were in the audience with me. People complain about audiences a lot – look at the comments on any online article about cinemas and you’ll find people crowing about how they prefer to watch at home on their massive TVs without mobile phones going off and exorbitantly priced popcorn – but I don’t think they’re much worse than they ever were. Sure, mobile phones are a pain, but who else remembers the chorus of chirruping digital watches sounding the hour back in the 80s?

So here’s a short list of some of my favourite cinema experiences. They’re not necessarily my favourite films, or my favourite venues – though there’s a certain amount of overlap – just a handful of examples where I could not possibly have had the same experience watching the film at home.

The Abyss, Cannon Cinema Rochdale, October 1989

The Cannon was my local cinema when I was growing up in Rochdale, and once I got the cinema bug it was where I went pretty much every weekend. The audience could be overly chatty if they weren’t engaged in the film, as happens when people go to the cinema for something to do rather than to see a particular film (do people still do that?). This would certainly irritate me during something like Sex, Lies and Videotape, but if the film was a crowdpleaser then it could be a definite plus. Among my favourites: Beetlejuice, Die Hard, and Gremlins 2 – especially that bit which is designed specifically to work in a cinema (you’ll know the one I mean if you’ve seen it).

I’ve picked The Abyss because of the audience’s interesting reaction. There’s a bit about three quarters of the way through when Ed Harris and Mary Elizabeth Mastrantonio are trapped in a sub with only one diving suit between them; he has to let her drown, drags her over to the main base, and try to revive her. He attempts mouth to mouth and chest compressions with no luck, getting increasingly desperate as the other characters tearfully urge him to accept the inevitable. He almost does, but then redoubles his efforts.

Throughout this whole sequence, the audience sat in silence, absolutely gripped. James Cameron had them in the palm of his hand. Until the moment that Our Heroine, who has been dead for several minutes, gives a choking splutter and revives. At that point, everyone fell about in mocking laughter.

Many of the reviews at the time singled out a later section of the film for criticism, but the film was a lost cause well before that moment when I saw it. I’ve never seen a film lose an audience so completely, before or since.

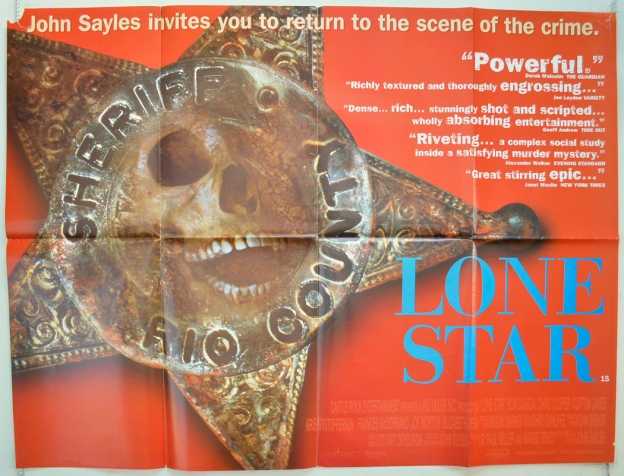

Lone Star, Cornerhouse Manchester, 1996

When my interest in film started moving beyond the mainstream, the Cornerhouse became my new favourite venue. Among the films I particularly remember would be Do the Right Thing, Land and Freedom, reissues of Mean Streets and The Wicker Man. I’ve picked Lone Star because it was followed by a Q&A with the writer/director, John Sayles. It wasn’t my first Sayles film (I’d seen Brother from Another Planet on TV, and City of Hope at the Hull Film Theatre) and it wasn’t even my first director Q&A (that was Isaac Julien’s Young Soul Rebels at the same venue). But it was the first time I was able to see in the flesh a filmmaker in whom I had developed a strong interest. I didn’t ask a question though.

The Blair Witch Project, Anjelika Film Center, New York, July 1999

I got lucky with this one. I was in New York on holiday when the Blair Witch Project opened, and I got to see it when the hype was only just starting off (a lot of people were disappointed when it finally reached the UK, and no wonder after so much build up). I’m not sure if I’d even heard of it before then. The film was in its second week of release, and only playing in two cinemas – the Anjelika in New York, and one in Los Angeles.

There was a screening, I think, every hour, and there were queues around the block, so the atmosphere was already good. Found footage shakycam isn’t everyone’s cup of tea (and there have been plenty of terrible examples of the form since) but the film worked for me. By the end of it, I was a wreck: my legs were shaking so much I had to hang on to the seats as I walked out.

One thing I particularly recall is that, due to America’s different rating system (where kids can watch pretty much anything so long as an adult takes them) there was a boy behind me who couldn’t have been much more than 11. “So are they all dead?” he asked his mother. “Well, I guess so, honey,” was he less-than-reassuring reply.

The guy next to me leant over as they got up to leave. “If I’d seen that film when I was that kid’s age,” he said, “it would have fucked me up for life.” I couldn’t disagree.

Bridesmaids, Curzon Cinema Clevedon, July 2011

I was Director of the Curzon Cinema at the time of Bridesmaids’ release, but I sometimes visited as a member of the audience – either to check the customer experience for myself, or because I wanted to see the film. This was a bit of both.

I felt a bit of trepidation as the hall filled up. Obviously I was happy it was busy, but I noticed that there was a slightly unusual mix of patrons – one half of the auditorium was filling up with the over 40 crowd (like many indie venues, this was the Curzon’s primary market) while the other half had a lot of teenagers. Different audience segments can have different ideas about what constitutes acceptable behaviour in a cinema, and what is unacceptably crude in a comedy.

I needn’t have worried; they all loved it. Although I wasn’t wild about the film myself, it’s a fact that comedy is one of the genres that are unquestionably better with a crowd. There’s nothing like the feeling I had that night as I listened to a couple of hundred people of varying ages, all united in laughter at a single, perfectly timed use of the word ‘cunt’.

Final Destination 5, Empire Leicester Square, August 2011

I wanted to include a festival visit to round off this piece, but to my surprise, I struggled to think of one. I’ve been to the Edinburgh Film Festival many times, and London a fair few, but I would usually see films at the daytime industry screenings rather than with the general public, which is a slightly different experience.

Then I remembered seeing Final Destination 5 at Frightfest. Horror is the other genre that is definitely better with a crowd (just with deaths taking the place of jokes), and this particular audience was predisposed to like it. It helped that the film was a cracker – great kills, and a nicely planned twist at the end – but few things are better than watching people dying horribly in the company of hundreds of like-minded viewers.

To close, here’s a clip from Joe Dante’s Matinee that perfectly encapsulates the anticipation of going to the cinema. That shot moving up to the stairs to the auditorium doors still sends a little shiver up my spine. Ironically, I didn’t see this one in the cinema.